by Richard Subber | Jun 29, 2020 | American history, History, Tidbits

“The Six Grandfathers”

It’s generally believed that Mt. Rushmore was an unremarkable pile of rock before the famous sculptures of presidents were done.

Gutzon Borglum and his son, Lincoln Borglum, did the work starting in 1927, and it was completed in 1941. The Borglums and their crews blasted more than 400,000 tons of stone off the face of the mountain in the Black Hills in Keystone, SD.

Here’s the unfamiliar back story: It wasn’t always called Mt. Rushmore (The granite bluff was named after Charles Rushmore, a wealthy New York lawyer, in 1885).

The Lakota Sioux name for the mountain had been “The Six Grandfathers” (Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe).

It’s too bad the federal government didn’t authorize carving their likenesses into the face of the bluff.

N.B. The image is of Mt. Rushmore in 1905.

* * * * * *

Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2020 All rights reserved.

Book review: The Snow Goose

…sensual drama, it’s eminently poetic…

by Paul Gallico

–

Above all: Poems of dawn and more with 73 free verse poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Apr 10, 2020 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, Revolutionary War

…and those hairy, smelly foreigners

Book review:

Red, White, and Black:

The Peoples of Early North America

by Gary B. Nash (b1933)

American historian

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, copyright 1974, 4th ed. 2000

362 pages

Red, White, and Black offers many partial answers to the question: in the 16th and 17th centuries, what did the First Americans think about the hairy, smelly people from Europe who invaded their country?

Nash offers a scholarly, fully informed, insightful account of the lifestyles and world views of the estimated 60-70 million indigenous people who had a variety of highly developed civilizations.

Some European promoters and some uninformed explorers and colonists reported that the “New World” was a “virgin wilderness,” but the first colonists were happy to steal the Native Americans’ food and delighted to be able to use their cultivated lands.

The misnamed Indians valiantly tried to maintain their way of life, but European diseases and European guns and steel tipped the balance for the much outnumbered invaders.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2020 All rights reserved.

Fire in the Lake (book review)

really, you should have read it in 1972…

by Frances FitzGerald

–

Writing Rainbows: Poems for Grown-Ups with 59 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Jan 10, 2020 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, World history

American leadership never was

what we thought it was…

Book review:

Fire in the Lake:

The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam

by Frances FitzGerald (b1940), a Pulitzer Prize winner

Boston: An Atlantic Monthly Press Book, Little Brown and Company, 1972

491 pages

I don’t know how much of an audience there was for Fire in the Lake in 1972. I feel confident in guessing there wasn’t enough.

The American war in Vietnam was far from over in 1972 when FitzGerald wrote this densely researched journalistic review of U. S. policies and actions and ignorance in Southeast Asia. She makes it easier to understand why the American war effort was doomed from its earliest phase.

You should read Fire in the Lake to get the whole story–that is, the whole story as it was knowable in 1972. Be prepared to acknowledge that much of what you previously believed—and thought you knew—was wrong.

The American commitment to “containing Communism” was prominent, and tragically uninformed.

South Vietnam was the wrong place to try to “contain Communism,” no matter what that might mean.

There are more than 58,000 names on the walls of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

Some of them are the names of my friends.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2020 All rights reserved.

Book review:

Joseph Brant and His World

“Brant was fully a Mohawk…”

by James Paxton

–

Seeing far: Selected poems with 47 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Jun 25, 2019 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, Revolutionary War

a new look…

Book review:

The British Are Coming:

The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777

by Rick Atkinson

New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2019.

776 pages

Atkinson offers an appealing mix of academic rigor and entertaining prose. This is both a history and an expertly rendered story about the early stages of the American Revolutionary War.

If you think you know a lot about this critical time during our history, read The British Are Coming to broaden your knowledge and your understanding. If you’re working at being a student of the Revolution, dig in.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2019 All rights reserved.

A glimpse of the millennial dawn…

witness to the song of the sea…

a nature poem

“Chanson de mer”

click here

Boz indeed!

Charles Dickens delivers,

in a fastidiously literary kind of way…

click here

–

Above all: Poems of dawn and more with 73 free verse poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Mar 30, 2019 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, World history

No, the “Great Man” theory won’t scour…

Book review:

The End of Greatness:

Why American Can’t Have

(and Doesn’t Want) Another Great President

by Aaron David Miller (b1949)

Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2014

280 pages

First things first: Miller’s title sets him up for failure. It defies even the murkiest conception of common sense to argue that Americans don’t want a great president. I hazard the guess that it’s impossible to define “great president” in a way that would satisfy most readers.

More substantially, The End of Greatness isn’t a worthwhile read for me because, right up front, Miller acknowledges his endorsement of the “Great Man” theory of historical understanding that was championed initially in the 1840s by the Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle. The theory is often cited but it has only quite diminished standing today, as most historians and informed thinkers believe that durable circumstances and the complex dynamics of human interaction have much more impact than “Great Men” on our lives and on history as it unfolds. So, Miller gets started on the wrong foot, and his arguments can’t overcome the narrowness of his analysis.

“Where are the giants of old, the transformers who changed the world and left great legacies?” Where are the leaders who “will author some incomparable, unparalleled, and ennobling achievement at home or on the world stage, an achievement likely to be seen or remembered as great or transformational?” Miller cites rebellions and revolutions as “crucibles for emerging leaders.”

He can’t escape defining “greatness” and offers: “defined generally as incomparable and unparalleled achievement that is nation- or even world-altering.” A couple pages later he digs the hole deeper when he equates greatness with military, political, economic and “soft” power. Incredibly, Miller declares “Greatness in the presidency may be rare, but it is both real and measurable,” and he temptingly alludes to “traces of greatness” in several contemporary presidents, while arguing “Greatness in the presidency is too rare to be relevant in our modern times.”

Miller makes it official on page 10: Lincoln was one of the great presidents. Lincoln once dismissed another man’s argument by saying “it won’t scour,” as 19th century farmers said that a plow “won’t scour” when it failed to easily let the clods slide off the plowshare.

I think Miller’s thesis won’t scour. He mistakenly asserts that a few great leaders should get much of the credit for history’s “transformations.” He frames his arguments with words that can’t be acceptably, explicitly defined on the grand historical scale that he uses: what is and what isn’t, specifically and unarguably, a “great legacy”? a “transformation”? an “unparalleled achievement”? a “trace of greatness”?

The End of Greatness relies on great big categories and a deceptive positive spin to discuss a little idea, and to make a gratuitous point that really can’t be proved or disproved.

Full disclosure: I didn’t read the whole book. The Introduction stopped me cold.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2019 All rights reserved.

We Were Soldiers Once…and Young

…too much death (book review)

Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore (ret.)

and Joseph L. Galloway

–

My first name was rain: A dreamery of poems with 53 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Jan 28, 2019 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History

“…conquerors who saw themselves

more as guardians…”

Book review:

The Comanche Empire

by Pekka Hämäläinen

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

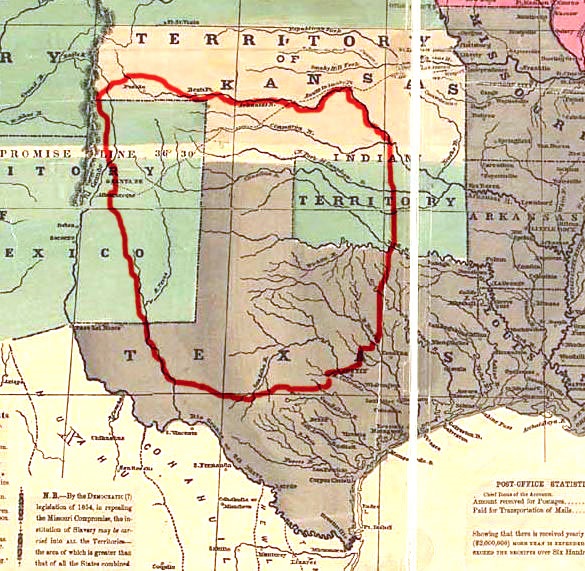

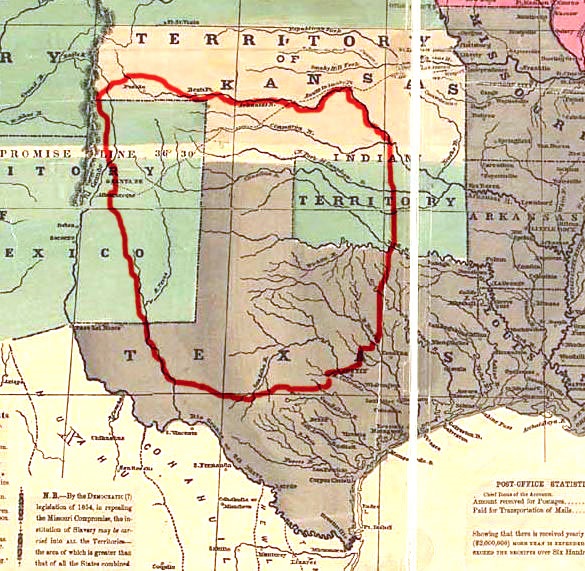

This book will change your mind about how the West was won.

Hint: The Comanches got there first.

The Comanches arrived obscurely in the American Southwest in 1706. The Comanche Empire provocatively makes the case that the Comanches created an imposing Southwestern American empire that spanned 150 years. They blunted the 18th century colonial ambitions of the Spanish in Mexico and the French in Louisiana, and stalled the westward thrust of Americans and the U.S. government until the middle of the 19th century. A broad coalition of Comanche rancheria chiefs throughout the territory of Comancheria first dominated the Apaches, eventually turned against their Ute allies, and commercially or militarily subjugated numerous lesser tribes.

Comanches managed a succession of peace treaties and conflicts with the Spaniards and completely blocked their repeated efforts to extend colonial settlements northward from Mexico. The political, commercial and military supremacy of the Comanches was based principally on their success in adopting and adapting Spanish horses for efficient transportation, military power, and a thriving and lucrative trade in horses throughout the Southwest.

Hämäläinen‘s central argument invites—indeed it obviously provokes—a reasonable dispute about the credibility of his claim for a Comanche empire. Clearly, in classical political or geopolitical usage, the claim is untenable, at least in part; the Comanche empire had neither fixed borders, nor a single self-sustaining centralized supreme authority, nor a durable bureaucracy, nor a definitive political structure.

Nevertheless, the Comanches had a respected, recurring broadly representative council of chiefs that planned and organized extensive raids, trading and other commerce, and military operations. Their hunting, pasturing, and trading territories had indistinct geographic borders that were never surveyed or adjudicated; Comanches never sought to occupy and permanently control any specifically delineated territory. In The Comanche Empire, Hämäläinen says they were “conquerors who saw themselves more as guardians than governors of the land and its bounties.” Nonetheless, the geographical extent of the their domains was well known, respected and enforced by the Comanches.

Nevertheless, the Comanches had a respected, recurring broadly representative council of chiefs that planned and organized extensive raids, trading and other commerce, and military operations. Their hunting, pasturing, and trading territories had indistinct geographic borders that were never surveyed or adjudicated; Comanches never sought to occupy and permanently control any specifically delineated territory. In The Comanche Empire, Hämäläinen says they were “conquerors who saw themselves more as guardians than governors of the land and its bounties.” Nonetheless, the geographical extent of the their domains was well known, respected and enforced by the Comanches.

Each Comanche rancheria had its own geographic territory, rigorous socio-military culture and hierarchical organization. The situational circumstances of Comanche military superiority, their control of trade and their ability through the decades to repeatedly impose and maintain obviously favorable terms in their treaty and trade agreements are undeniable evidence of the Comanches’ extended dominance of terrain, physical resources, culture and commerce, and, not least in importance, the Spanish and French colonial enterprises that sought to compete with them.

For decades the Comanches set the terms of their success; no competing power could defeat them, and no Indians or Europeans could evade the Comanches’ dominance in their domain.

It becomes obvious: the Comanches created a de facto empire.

Ultimately, they were marginalized by a combination of drought that constrained their bison hunting and weakened their pastoral horse culture, disruption of trade that limited their access to essential carbohydrate foodstuffs, epidemic disease that repeatedly thinned the Comanche populations, predatory bison hunting by the Americans in the early 1870s that wiped out the Indians’ essential food resource, and, finally, by the irresistible tide of U.S. government-sponsored westward migration that pushed American citizens into Comanche territory.

Too bad the Comanches left no accounts of their own. It would be fascinating to hear this story in their own words.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2019 All rights reserved.

Up for the counting

…he picks up the rhythm…(a poem)

“Numerology”

click here

Above all: Poems of dawn and more with 73 free verse poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

Nevertheless, the Comanches had a respected, recurring broadly representative council of chiefs that planned and organized extensive raids, trading and other commerce, and military operations. Their hunting, pasturing, and trading territories had indistinct geographic borders that were never surveyed or adjudicated; Comanches never sought to occupy and permanently control any specifically delineated territory. In The Comanche Empire,

Nevertheless, the Comanches had a respected, recurring broadly representative council of chiefs that planned and organized extensive raids, trading and other commerce, and military operations. Their hunting, pasturing, and trading territories had indistinct geographic borders that were never surveyed or adjudicated; Comanches never sought to occupy and permanently control any specifically delineated territory. In The Comanche Empire,