by Richard Subber | Jun 25, 2019 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, Revolutionary War

a new look…

Book review:

The British Are Coming:

The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777

by Rick Atkinson

New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2019.

776 pages

Atkinson offers an appealing mix of academic rigor and entertaining prose. This is both a history and an expertly rendered story about the early stages of the American Revolutionary War.

If you think you know a lot about this critical time during our history, read The British Are Coming to broaden your knowledge and your understanding. If you’re working at being a student of the Revolution, dig in.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2019 All rights reserved.

A glimpse of the millennial dawn…

witness to the song of the sea…

a nature poem

“Chanson de mer”

click here

Boz indeed!

Charles Dickens delivers,

in a fastidiously literary kind of way…

click here

–

Above all: Poems of dawn and more with 73 free verse poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Mar 30, 2019 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, World history

No, the “Great Man” theory won’t scour…

Book review:

The End of Greatness:

Why American Can’t Have

(and Doesn’t Want) Another Great President

by Aaron David Miller (b1949)

Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2014

280 pages

First things first: Miller’s title sets him up for failure. It defies even the murkiest conception of common sense to argue that Americans don’t want a great president. I hazard the guess that it’s impossible to define “great president” in a way that would satisfy most readers.

More substantially, The End of Greatness isn’t a worthwhile read for me because, right up front, Miller acknowledges his endorsement of the “Great Man” theory of historical understanding that was championed initially in the 1840s by the Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle. The theory is often cited but it has only quite diminished standing today, as most historians and informed thinkers believe that durable circumstances and the complex dynamics of human interaction have much more impact than “Great Men” on our lives and on history as it unfolds. So, Miller gets started on the wrong foot, and his arguments can’t overcome the narrowness of his analysis.

“Where are the giants of old, the transformers who changed the world and left great legacies?” Where are the leaders who “will author some incomparable, unparalleled, and ennobling achievement at home or on the world stage, an achievement likely to be seen or remembered as great or transformational?” Miller cites rebellions and revolutions as “crucibles for emerging leaders.”

He can’t escape defining “greatness” and offers: “defined generally as incomparable and unparalleled achievement that is nation- or even world-altering.” A couple pages later he digs the hole deeper when he equates greatness with military, political, economic and “soft” power. Incredibly, Miller declares “Greatness in the presidency may be rare, but it is both real and measurable,” and he temptingly alludes to “traces of greatness” in several contemporary presidents, while arguing “Greatness in the presidency is too rare to be relevant in our modern times.”

Miller makes it official on page 10: Lincoln was one of the great presidents. Lincoln once dismissed another man’s argument by saying “it won’t scour,” as 19th century farmers said that a plow “won’t scour” when it failed to easily let the clods slide off the plowshare.

I think Miller’s thesis won’t scour. He mistakenly asserts that a few great leaders should get much of the credit for history’s “transformations.” He frames his arguments with words that can’t be acceptably, explicitly defined on the grand historical scale that he uses: what is and what isn’t, specifically and unarguably, a “great legacy”? a “transformation”? an “unparalleled achievement”? a “trace of greatness”?

The End of Greatness relies on great big categories and a deceptive positive spin to discuss a little idea, and to make a gratuitous point that really can’t be proved or disproved.

Full disclosure: I didn’t read the whole book. The Introduction stopped me cold.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2019 All rights reserved.

We Were Soldiers Once…and Young

…too much death (book review)

Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore (ret.)

and Joseph L. Galloway

–

My first name was rain: A dreamery of poems with 53 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Jan 28, 2019 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History

“…conquerors who saw themselves

more as guardians…”

Book review:

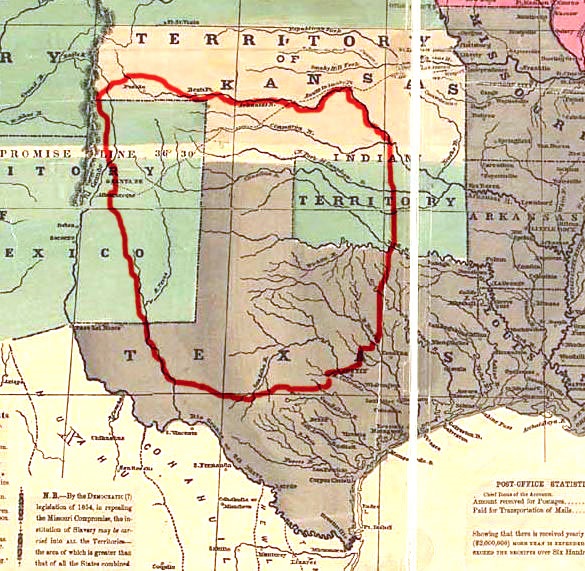

The Comanche Empire

by Pekka Hämäläinen

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

This book will change your mind about how the West was won.

Hint: The Comanches got there first.

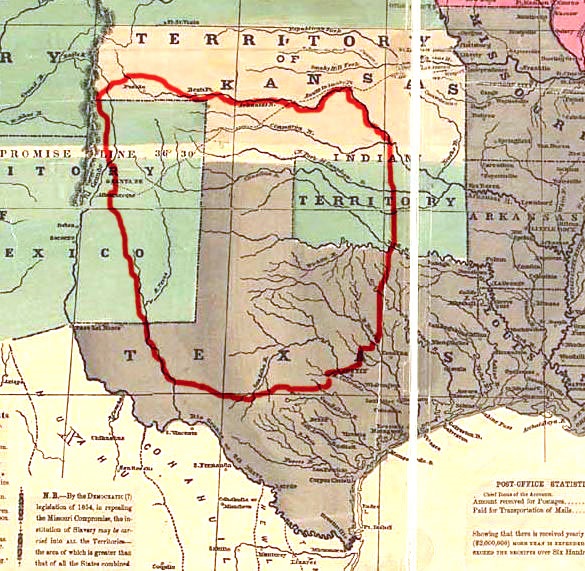

The Comanches arrived obscurely in the American Southwest in 1706. The Comanche Empire provocatively makes the case that the Comanches created an imposing Southwestern American empire that spanned 150 years. They blunted the 18th century colonial ambitions of the Spanish in Mexico and the French in Louisiana, and stalled the westward thrust of Americans and the U.S. government until the middle of the 19th century. A broad coalition of Comanche rancheria chiefs throughout the territory of Comancheria first dominated the Apaches, eventually turned against their Ute allies, and commercially or militarily subjugated numerous lesser tribes.

Comanches managed a succession of peace treaties and conflicts with the Spaniards and completely blocked their repeated efforts to extend colonial settlements northward from Mexico. The political, commercial and military supremacy of the Comanches was based principally on their success in adopting and adapting Spanish horses for efficient transportation, military power, and a thriving and lucrative trade in horses throughout the Southwest.

Hämäläinen‘s central argument invites—indeed it obviously provokes—a reasonable dispute about the credibility of his claim for a Comanche empire. Clearly, in classical political or geopolitical usage, the claim is untenable, at least in part; the Comanche empire had neither fixed borders, nor a single self-sustaining centralized supreme authority, nor a durable bureaucracy, nor a definitive political structure.

Nevertheless, the Comanches had a respected, recurring broadly representative council of chiefs that planned and organized extensive raids, trading and other commerce, and military operations. Their hunting, pasturing, and trading territories had indistinct geographic borders that were never surveyed or adjudicated; Comanches never sought to occupy and permanently control any specifically delineated territory. In The Comanche Empire, Hämäläinen says they were “conquerors who saw themselves more as guardians than governors of the land and its bounties.” Nonetheless, the geographical extent of the their domains was well known, respected and enforced by the Comanches.

Nevertheless, the Comanches had a respected, recurring broadly representative council of chiefs that planned and organized extensive raids, trading and other commerce, and military operations. Their hunting, pasturing, and trading territories had indistinct geographic borders that were never surveyed or adjudicated; Comanches never sought to occupy and permanently control any specifically delineated territory. In The Comanche Empire, Hämäläinen says they were “conquerors who saw themselves more as guardians than governors of the land and its bounties.” Nonetheless, the geographical extent of the their domains was well known, respected and enforced by the Comanches.

Each Comanche rancheria had its own geographic territory, rigorous socio-military culture and hierarchical organization. The situational circumstances of Comanche military superiority, their control of trade and their ability through the decades to repeatedly impose and maintain obviously favorable terms in their treaty and trade agreements are undeniable evidence of the Comanches’ extended dominance of terrain, physical resources, culture and commerce, and, not least in importance, the Spanish and French colonial enterprises that sought to compete with them.

For decades the Comanches set the terms of their success; no competing power could defeat them, and no Indians or Europeans could evade the Comanches’ dominance in their domain.

It becomes obvious: the Comanches created a de facto empire.

Ultimately, they were marginalized by a combination of drought that constrained their bison hunting and weakened their pastoral horse culture, disruption of trade that limited their access to essential carbohydrate foodstuffs, epidemic disease that repeatedly thinned the Comanche populations, predatory bison hunting by the Americans in the early 1870s that wiped out the Indians’ essential food resource, and, finally, by the irresistible tide of U.S. government-sponsored westward migration that pushed American citizens into Comanche territory.

Too bad the Comanches left no accounts of their own. It would be fascinating to hear this story in their own words.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2019 All rights reserved.

Up for the counting

…he picks up the rhythm…(a poem)

“Numerology”

click here

Above all: Poems of dawn and more with 73 free verse poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Jan 5, 2019 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History

He writes prose like a poet…

Book review:

Cold Mountain

by Charles Frazier (b1950)

New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1997

356 pages

Winner of the U. S. National Book Award for Fiction

Cold Mountain is Frazier’s first novel. I expect that any writer who has read it has murmured many, many times: “I wish I’d written that.”

Most likely you know the plot of this abundantly appealing love story of the American Civil War: a narrative of a resilient, ingenuous maid with a poetic willingness to live a full life, and an honest, humane Confederate soldier who doggedly treks the length of North Carolina to get home to her. Both Ada and Inman touch and walk through a world that is richly colored and flamboyantly populated by Frazier’s imagination, and by his peerless command of the right words.

Cold Mountain reaches quite deep into the reader’s mind and heart. Frazier’s prose invites participation. I realized, near the end, that I was not reading the book. I experienced the book. It is a rare treat for a book lover.

Frazier’s vocabulary is abundant and provocative. For my taste, the characters of Veasey and Stobrod are elaborated just a bit too much, and I wouldn’t have minded knowing a bit more of Ruby’s innocent, boundless wisdom.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2019 All rights reserved.

Book review: The Cradle Place

by Thomas Lux

poems wrapped in a wet rag…

–

In other words: Poems for your eyes and ears with 64 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Dec 19, 2018 | Book reviews, Books, History

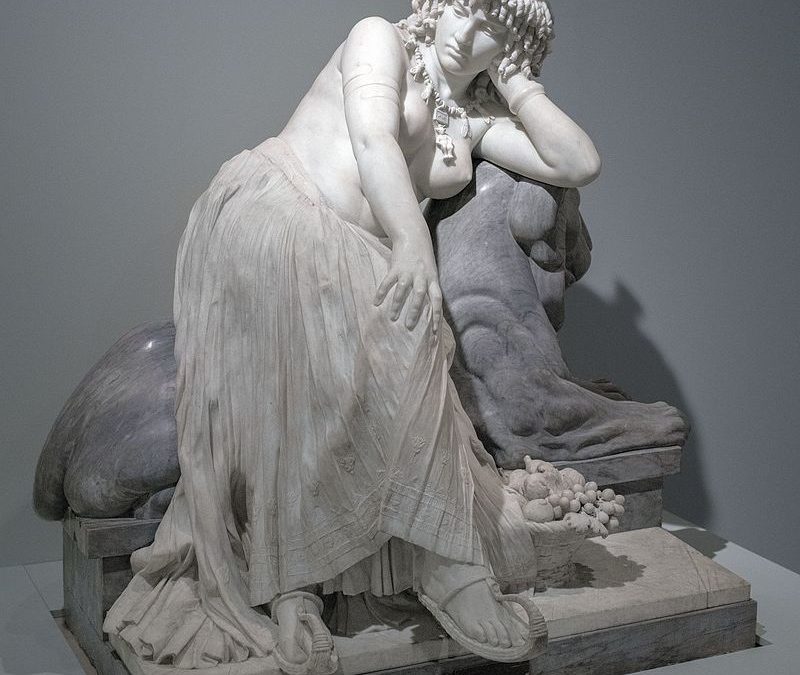

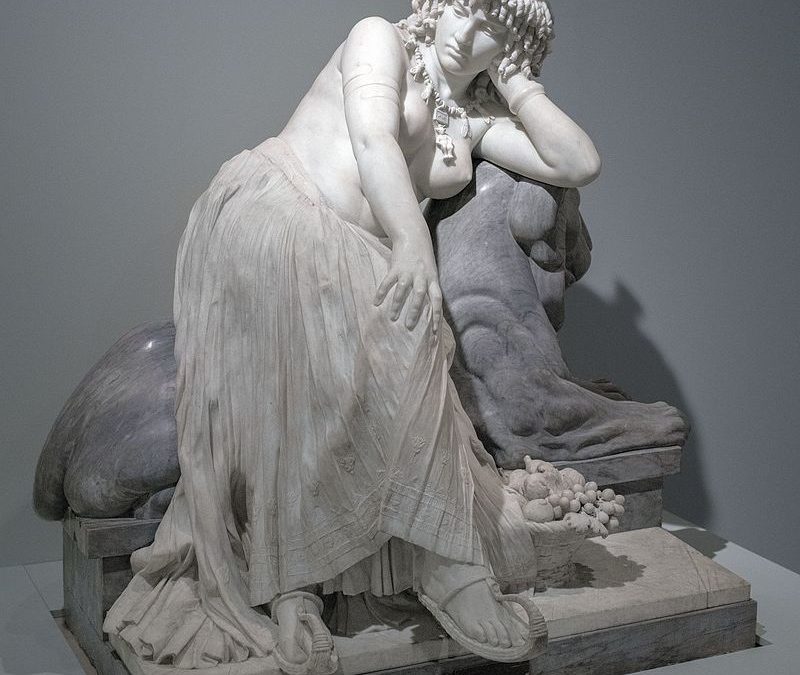

Cleopatra: she was a taker…

Book review:

Cleopatra: A Life

by Stacy Schiff

New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2010

Schiff is a Pulitzer Prize winner

Cleopatra: A Life is a compelling, stunningly contextual biography. It makes sense of the canonical, jumbled, and inconsistent biographical accounts of ancient writers who didn’t know Cleopatra personally. In many ways, it’s more modern than ancient.

Cleopatra, apparently, was the richest person in the known Western world while she reigned as Cleopatra VII, the last Pharaoh of the Ptolemaic dynasty, and the last queen of Egypt.

As a ruler, she had her ups and downs, but during her ups, she was the most powerful ruler in that world.

Cleopatra was a goddess, a celebrity, a winning general, a political mastermind, a serial murderess, an utterly enchanting lover, a startlingly well-educated, knowledgeable, and curious mover and shaker…think of Isis, Madonna, Patton, Golda Meir, Lucrezia Borgia, Marie Curie, and Aphrodite combined in a Type A personality with more or less unlimited worldly power…

The political action in Cleopatra: A Life is, sad to say, is all too familiar….I want to emphasize the context that Schiff describes: entirely recognizable governmental and organizational failures/corruption were pervasive in Cleopatra’s Egypt, and they are easily described and understood in modern terms.

Venal bureaucrats “walked like an Egyptian” …

you wouldn’t have had to search too long or too hard in Alexandria circa 50 BC to find one. You say “no surprise”? Well, of course, no surprise.

The Egyptian empire governed by Cleopatra was notoriously and vastly bureaucratized, and possibly the most significant enabling factor was the rich productivity of the Nile delta, renewed (almost) annually by the life-giving flood of the Nile. At the time, this stupefying agricultural abundance fed not only Egypt but also Rome—this was one factor motivating the famous attentions of Caesar and Marc Antony to the affairs in Egypt, including Cleopatra.

The riches of Egypt created an almost failsafe environment for heedless waste and mismanagement without fatal consequences—and also corruption at a level that everyone with any say in the matter could easily tolerate. Cleopatra, and her siblings and forebears, in the Ptolemaic dynasty were divinely in charge, with no effective restraint except the occasional Roman legion or two, and Rome was easily bought off. There was more than enough booty to go around for all who could claim a share.

At the time, there were persistent royal proclamations urging the ideal “good official” to be “vigilant, upright, a beacon of goodwill.” These were perhaps well-intentioned but wholly ineffective. There was too much booty to be had and insufficient penalties for taking more than one’s decent share. And the people of Cleopatra’s Egypt? These were descendants of the people who perhaps willingly labored to build the pyramids, these were people who thought Cleopatra was a goddess, these were people who believed in the everlasting rectitude of the dynastic and religious hierarchies that manifestly benefited a tiny elite…why did the people embrace all of that?

Cleopatra: A Life is a good read…you might have to remind yourself from time to time that none of it was written by Gordon Gekko.

Click here for Gekko’s “greed is good” speech

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2018 All rights reserved.

Book review: The House by the Sea

May Sarton’s travels, in her mind…

click here

–

Seeing far: Selected poems with 47 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Nov 28, 2018 | Book reviews, Books, History

“…historical-mindedness…”

—say what?

Book review:

A Preface to History

by Carl G. Gustavson

New York, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1955

222 pages

A Preface to History was expressly designed for college freshmen in the post-WWII context of ingenuous idealism about getting a good liberal arts education in college.

Gustavson’s approach is much less than satisfactory. His advice to students is straightforward and somewhat naively businesslike in the sense that the student is encouraged to be “historical-minded.” From his preface: “It would seem to be in the interests of the [historian’s] profession to stress the elements of the historical approach itself, which is basic in many courses besides history proper and which is an ingredient of the liberal arts mind.” Indeed.

Seven characteristics of historical-mindedness are carefully mentioned by Gustavson—including “A natural curiosity as to what underlies the surface appearances of any historical event,” and “The historian knows that each situation and event is unique.”

Indeed.

Notably, the word “historiography” is not in the index of A Preface to History.

A serious and well-informed student of history probably will not conclude that A Preface to History is essential for her continued learning.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2018 All rights reserved.

Book review: The House by the Sea

May Sarton’s travels, in her mind…

click here

–

In other words: Poems for your eyes and ears with 64 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

Nevertheless, the Comanches had a respected, recurring broadly representative council of chiefs that planned and organized extensive raids, trading and other commerce, and military operations. Their hunting, pasturing, and trading territories had indistinct geographic borders that were never surveyed or adjudicated; Comanches never sought to occupy and permanently control any specifically delineated territory. In The Comanche Empire,

Nevertheless, the Comanches had a respected, recurring broadly representative council of chiefs that planned and organized extensive raids, trading and other commerce, and military operations. Their hunting, pasturing, and trading territories had indistinct geographic borders that were never surveyed or adjudicated; Comanches never sought to occupy and permanently control any specifically delineated territory. In The Comanche Empire,