by Richard Subber | Feb 12, 2021 | American history, Book reviews, Books, Democracy, History, Power and inequality

…doing more good in America…

Book review:

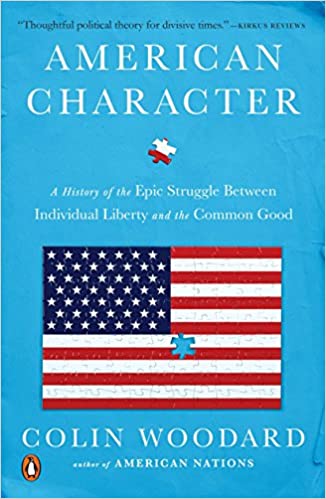

American Character:

A History of the Epic Struggle

Between Individual Liberty and the Common Good

Colin Woodard (b1968)

Journalist

New York: Viking, 2016

308 pages

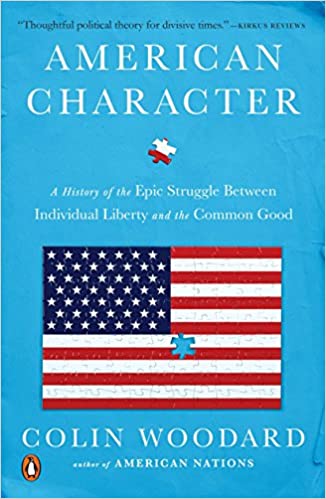

American Character is intuitive and informative analysis of what makes Americans tick, politically.

Woodard says we need to promote “fairness” in all its meanings if we want a shot at changing the success stories of Trump/laissez fair Republicans/Tea Party/the oligarchs. I reluctantly use the word “fairness” without any pretense of conveying the fullness of his meaning. It means a lot, in different ways—seriously, meaningfully, it’s different strokes for different folks.

I’m gonna read American Character again.

It’s easy to understand what Woodard is saying. He offers a sane and credible strategy for doing more good in America for all Americans.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2021 All rights reserved.

How does a poem end?

“Finis,” my thoughts (my poem)

–

Above all: Poems of dawn and more with 73 free verse poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Dec 29, 2020 | Book reviews, Books, History, World history

the “milliohnim” and “the promised land”

Book review:

Thieves in the Night:

Chronicle of an Experiment

by Arthur Koestler (1905-1983)

The Macmillan Company, New York, 1946

357 pages

Koestler, a Hungarian-British writer and journalist, more famously wrote Darkness at Noon, a critique of Communism and totalitarianism.

Thieves in the Night, written later, is a gently powerful story. Koestler recounts the travails and limited joys of only a few of the “milliohnim” who sought a promised land. His characters are Jews, creating new settlements on purchased Arab land in the Holy Land, prior to World War II.

Men and women who create settlements live a tough life. A reader like me learns almost too much about the vagaries and drudgery of deliberately, fully conscious communal life on Ezra’s Tower, an isolated hilltop in Galilee. First, establish the security perimeter, then erect the watchtower, build the children’s dorm, construct the cowshed, set up the showers…in that order. The dining hall, the sleeping huts for the men and women, and the lavatories are to be built later.

The Mukhtar and his clan in the nearby Arab village do not welcome the Hebrew newcomers. Soon, the leader of the village delegation gives morbid advice to the settlers: “You young fools and children of death, you don’t know what may happen to you.” Bauman responds curtly: “We are prepared.” The Jewish settlement at Ezra’s Tower is not a resort.

The story of the settlers’ life at Ezra’s Tower is mostly drab. Koestler’s exploration of their mindset, their politics, their philosophy, and their religion all swirled together is stunning. Their aspirations and their misgivings, and their palpable legacy of homelessness and their transforming experiences, are irresistible.

Thieves in the Night is an adventure for the open and inquiring mind. Occasional sympathetic despair is a perfectly understandable reaction.

After you read this novel, look around you and ask yourself: do you see things a bit differently? Do you like your new conception of “a thief in the night.”

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2020 All rights reserved.

–

Old Friends (book review)

Tracy Kidder tells so much truth about old age…

–

Above all: Poems of dawn and more with 73 free verse poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Sep 22, 2020 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, Politics

…the last battle never comes…

Book review:

We Were Soldiers Once…and Young

Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore (ret.) and Joseph L. Galloway

New York: Random House, 1992

412 pages

Like Moore and Galloway, I salute the brave American and North Vietnamese soldiers who fought and died in the Ia Drang Valley in November 1965 in the first major combat action of the War in Vietnam.

We Were Soldiers Once…and Young is a bloody testament to the grinding horror of war. It’s too much to read all at once. It has too much death.

A North Vietnamese commander who was on the ground in the valley recalled, many years after the war, that his guiding principle had been “win the first battle.”

You and I know that he forgot to mention that no one knows how to win the last battle and end all of it.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2020 All rights reserved.

A Farewell to Arms (book review)

classic Ernest Hemingway

with relentlessly realistic dialogue…

–

As with another eye: Poems of exactitude with 55 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Sep 13, 2020 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, Revolutionary War

Book review:

An Empire on the Edge:

How Britain Came to Fight America

by Nick Bunker

Here’s the short version of Nick Bunker’s thesis:

King George and his government

let the North American colonies slip from their grasp.

A newcomer to the history of the American Revolution might think that this book is a cockeyed way to learn about the “shot heard ‘round the world” and the consequences of the shooting at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775.

An informed student of the Revolutionary War probably will find much new material in Bunker’s relentlessly detailed An Empire on the Edge: How Britain Came to Fight America.

On our side of the pond, we don’t have much opportunity to consider the war or the revolution from the British point of view.

Bunker offers devastating detail about the ill-informed, patronizing, self-serving, doctrinaire, and sometimes feckless actions of Lord North and the British government in the years that led to the sanguinary clash of British regulars and American farmers-militiamen on the road from Concord, through Lexington, to Boston on “that famous day and year.”

An Empire on the Edge offers extensive documentation confirming that the British leaders were largely ignorant of the scope and depth of colonial antipathy toward the various punitive measures that Britain sought to impose in North America, as early as 1765 (the Stamp Act) and continuing to the final, ill-fated steps to chastise the city of Boston after the notorious Tea Party in late 1773.

Bunker describes the half-cocked military moves by Lord North and his ministers in the years leading up to the disastrous outing to Lexington-Concord. The king and his government were not prepared to wage war successfully in North America, partly because they waited too long to believe that the colonists actually would fight, and partly because they disdained the colonials’ fighting capacity, and partly because they put higher priority on their Caribbean sugar colonies, and partly because they were pre-occupied with the military threat posed by France and various European intrigues.

Bunker doesn’t speculate on a question that occurs to me: after that first shot was fired at Lexington, did the British really commit themselves to winning the war?

Bunker doesn’t speculate on a question that occurs to me: after that first shot was fired at Lexington, did the British really commit themselves to winning the war?

The king and his government made the commitment to fight. They did not, however, at any time before or during the war, commit all the king’s horses and all the king’s men to the military campaign to regain dominion in North America. As the fighting began, a British victory was not immediately feasible. Perhaps it did not become feasible.

Bunker’s analysis of the planning and wrangling in Lord North’s war room suggests that the British wanted to win, but never pushed the right strategic buttons to bring victory within their grasp.

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2016 All rights reserved.

———

Book review: An Empire Divided

King George and his ministers

wanted the Caribbean sugar islands

more than they wanted the 13 colonies…

by Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy

–

Seeing far: Selected poems with 47 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

by Richard Subber | Jun 29, 2020 | American history, History, Tidbits

“The Six Grandfathers”

It’s generally believed that Mt. Rushmore was an unremarkable pile of rock before the famous sculptures of presidents were done.

Gutzon Borglum and his son, Lincoln Borglum, did the work starting in 1927, and it was completed in 1941. The Borglums and their crews blasted more than 400,000 tons of stone off the face of the mountain in the Black Hills in Keystone, SD.

Here’s the unfamiliar back story: It wasn’t always called Mt. Rushmore (The granite bluff was named after Charles Rushmore, a wealthy New York lawyer, in 1885).

The Lakota Sioux name for the mountain had been “The Six Grandfathers” (Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe).

It’s too bad the federal government didn’t authorize carving their likenesses into the face of the bluff.

N.B. The image is of Mt. Rushmore in 1905.

* * * * * *

Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2020 All rights reserved.

Book review: The Snow Goose

…sensual drama, it’s eminently poetic…

by Paul Gallico

–

Above all: Poems of dawn and more with 73 free verse poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Apr 10, 2020 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, Revolutionary War

…and those hairy, smelly foreigners

Book review:

Red, White, and Black:

The Peoples of Early North America

by Gary B. Nash (b1933)

American historian

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, copyright 1974, 4th ed. 2000

362 pages

Red, White, and Black offers many partial answers to the question: in the 16th and 17th centuries, what did the First Americans think about the hairy, smelly people from Europe who invaded their country?

Nash offers a scholarly, fully informed, insightful account of the lifestyles and world views of the estimated 60-70 million indigenous people who had a variety of highly developed civilizations.

Some European promoters and some uninformed explorers and colonists reported that the “New World” was a “virgin wilderness,” but the first colonists were happy to steal the Native Americans’ food and delighted to be able to use their cultivated lands.

The misnamed Indians valiantly tried to maintain their way of life, but European diseases and European guns and steel tipped the balance for the much outnumbered invaders.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2020 All rights reserved.

Fire in the Lake (book review)

really, you should have read it in 1972…

by Frances FitzGerald

–

Writing Rainbows: Poems for Grown-Ups with 59 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

Bunker doesn’t speculate on a question that occurs to me: after that first shot was fired at Lexington, did the British really commit themselves to winning the war?

Bunker doesn’t speculate on a question that occurs to me: after that first shot was fired at Lexington, did the British really commit themselves to winning the war?