by Richard Subber | Nov 3, 2021 | American history, Book reviews, Books, Democracy, History, Politics

the “public watchdog,” as if…

Book review:

-30- The Collapse

of the Great American Newspaper

Charles M. Madigan, ed.

Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, Publisher, 2007

Madigan collected 15 commentaries on the continuing decline of the American newspaper industry and the woeful prospects for its improvement or survival.

The authors of Collapse do not offer predictions, but the adverse circumstances they describe as existing or possible seem all too real almost 15 years later.

Community newspapers have mostly disappeared or shriveled in vitality and importance.

Big city newspapers have been transformed into cash conduits by profit-seeking money managers, who as a group don’t care about doing or preserving the popular (and dubious) legacy concept of journalism as “a public watchdog.”

At every level of government, from township zoning hearing board to U.S. Congress, fewer and fewer reporters—or no reporters—are showing up to observe what’s going on and report it to a citizenry that historically has never wanted to pay the full cost of getting “the news.”

The basic business model of newspaper owners today is: soak the aging, shriveling group of home delivery subscribers for as much as they will pay, and soak the shriveling group of newspaper advertisers for as much as they will pay, for as long as they’re willing to pay. One by one, newspapers are disappearing.

For example, the seven-day home delivery price of The Boston Globe is about $25/week, or almost $1,300/year.

Do you remember how much a newspaper cost when you were a kid?

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2021 All rights reserved.

We Were Soldiers Once…and Young

…too much death (book review)

Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore (ret.)

and Joseph L. Galloway

–

My first name was rain: A dreamery of poems with 53 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Jun 22, 2021 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, Politics, Power and inequality, World history

profitable, powerful, vicious…

Book review:

For All the Tea in China:

How England Stole the World’s Favorite Drink

and Changed History

by Sarah Rose

New York: Viking, Penguin Group, 2010

This is a credible account of how tea from China became a worldwide drink.

With commanding competence, Rose relates the intrepid life of Robert Fortune, and the depressingly familiar tale of a giant corporation running amok.

The East India Company in England was an extremely vicious, extremely powerful, and extremely profitable company for more than two hundred years. It was tea from the East India Company that got dumped into Boston harbor on December 16, 1773. After a bloody 1857 war of its own making in India, the company was abruptly dissolved by the British Parliament. Rose says: “…the company had amassed possessions to rival Charlemagne’s and created an empire on which the sun never set; it was the first global multinational and the largest corporation history has ever known. Yet it failed spectacularly at one significant task: to govern India in peace.” No surprise there.

For my taste, the greater value of For All the Tea in China is the examination of how the commerce and consumption of tea shaped worldwide politics, warfare, and society. Tea reduced famine in Europe. Tea taxes financed Britain’s imperial expansion. Increased tea drinking—and increased sugar consumption—made the British sugar colonies important in British commerce and politics. Centuries of monopoly in tea production and engagement with Europeans altered the political and cultural development of China.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2021 All rights reserved.

Book review: American Colonies

So many and so much

came before the Pilgrims

by Alan Taylor

–

Writing Rainbows: Poems for Grown-Ups with 59 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Jun 5, 2021 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, Human Nature, Politics

…the Irish weren’t the only ones…

Book review:

How the Irish Became White

by Noel Ignatiev (1940-2019)

American author and historian

New York: Routledge, 1995

Ignatiev offers enough detail and context to satisfy historians of every stripe.

For the less ambitious reader, there may be a bit more than she cares to know in How the Irish Became White.

Of course, I certainly don’t presume to summarize the author’s careful exposition in 233 pages.

If you really want to know more about how non-black immigrants allowed and persuaded themselves to buy in to the systemic racism that flourished in America since the 17th century, dig in to How the Irish Became White.

One sure point is: don’t pick on the Irish exclusively. They certainly weren’t alone in their transgressions.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2021 All rights reserved.

We Were Soldiers Once…and Young

…way too much death (book review)

Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore (ret.)

and Joseph L. Galloway

–

Above all: Poems of dawn and more with 73 free verse poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Feb 12, 2021 | American history, Book reviews, Books, Democracy, History, Power and inequality

…doing more good in America…

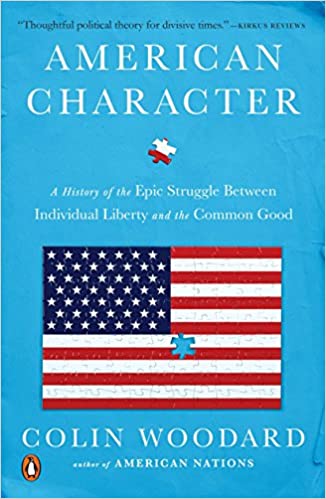

Book review:

American Character:

A History of the Epic Struggle

Between Individual Liberty and the Common Good

Colin Woodard (b1968)

Journalist

New York: Viking, 2016

308 pages

American Character is intuitive and informative analysis of what makes Americans tick, politically.

Woodard says we need to promote “fairness” in all its meanings if we want a shot at changing the success stories of Trump/laissez fair Republicans/Tea Party/the oligarchs. I reluctantly use the word “fairness” without any pretense of conveying the fullness of his meaning. It means a lot, in different ways—seriously, meaningfully, it’s different strokes for different folks.

I’m gonna read American Character again.

It’s easy to understand what Woodard is saying. He offers a sane and credible strategy for doing more good in America for all Americans.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2021 All rights reserved.

How does a poem end?

“Finis,” my thoughts (my poem)

–

Above all: Poems of dawn and more with 73 free verse poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Sep 22, 2020 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, Politics

…the last battle never comes…

Book review:

We Were Soldiers Once…and Young

Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore (ret.) and Joseph L. Galloway

New York: Random House, 1992

412 pages

Like Moore and Galloway, I salute the brave American and North Vietnamese soldiers who fought and died in the Ia Drang Valley in November 1965 in the first major combat action of the War in Vietnam.

We Were Soldiers Once…and Young is a bloody testament to the grinding horror of war. It’s too much to read all at once. It has too much death.

A North Vietnamese commander who was on the ground in the valley recalled, many years after the war, that his guiding principle had been “win the first battle.”

You and I know that he forgot to mention that no one knows how to win the last battle and end all of it.

* * * * * *

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2020 All rights reserved.

A Farewell to Arms (book review)

classic Ernest Hemingway

with relentlessly realistic dialogue…

–

As with another eye: Poems of exactitude with 55 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

* * * * * *

by Richard Subber | Sep 13, 2020 | American history, Book reviews, Books, History, Revolutionary War

Book review:

An Empire on the Edge:

How Britain Came to Fight America

by Nick Bunker

Here’s the short version of Nick Bunker’s thesis:

King George and his government

let the North American colonies slip from their grasp.

A newcomer to the history of the American Revolution might think that this book is a cockeyed way to learn about the “shot heard ‘round the world” and the consequences of the shooting at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775.

An informed student of the Revolutionary War probably will find much new material in Bunker’s relentlessly detailed An Empire on the Edge: How Britain Came to Fight America.

On our side of the pond, we don’t have much opportunity to consider the war or the revolution from the British point of view.

Bunker offers devastating detail about the ill-informed, patronizing, self-serving, doctrinaire, and sometimes feckless actions of Lord North and the British government in the years that led to the sanguinary clash of British regulars and American farmers-militiamen on the road from Concord, through Lexington, to Boston on “that famous day and year.”

An Empire on the Edge offers extensive documentation confirming that the British leaders were largely ignorant of the scope and depth of colonial antipathy toward the various punitive measures that Britain sought to impose in North America, as early as 1765 (the Stamp Act) and continuing to the final, ill-fated steps to chastise the city of Boston after the notorious Tea Party in late 1773.

Bunker describes the half-cocked military moves by Lord North and his ministers in the years leading up to the disastrous outing to Lexington-Concord. The king and his government were not prepared to wage war successfully in North America, partly because they waited too long to believe that the colonists actually would fight, and partly because they disdained the colonials’ fighting capacity, and partly because they put higher priority on their Caribbean sugar colonies, and partly because they were pre-occupied with the military threat posed by France and various European intrigues.

Bunker doesn’t speculate on a question that occurs to me: after that first shot was fired at Lexington, did the British really commit themselves to winning the war?

Bunker doesn’t speculate on a question that occurs to me: after that first shot was fired at Lexington, did the British really commit themselves to winning the war?

The king and his government made the commitment to fight. They did not, however, at any time before or during the war, commit all the king’s horses and all the king’s men to the military campaign to regain dominion in North America. As the fighting began, a British victory was not immediately feasible. Perhaps it did not become feasible.

Bunker’s analysis of the planning and wrangling in Lord North’s war room suggests that the British wanted to win, but never pushed the right strategic buttons to bring victory within their grasp.

Book review. Copyright © Richard Carl Subber 2016 All rights reserved.

———

Book review: An Empire Divided

King George and his ministers

wanted the Caribbean sugar islands

more than they wanted the 13 colonies…

by Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy

–

Seeing far: Selected poems with 47 free verse and haiku poems,

and the rest of my poetry books are for sale on Amazon (paperback and Kindle)

and free in Kindle Unlimited, search Amazon for “Richard Carl Subber”

Bunker doesn’t speculate on a question that occurs to me: after that first shot was fired at Lexington, did the British really commit themselves to winning the war?

Bunker doesn’t speculate on a question that occurs to me: after that first shot was fired at Lexington, did the British really commit themselves to winning the war?